Brief Summary

This text is a detailed exposition on the Yoga Vasistha, focusing on dispassion, the behavior of seekers, and the nature of creation. It emphasizes the importance of rational spirituality, self-effort, and understanding the illusory nature of the world to achieve liberation. Key points include:

- The Yoga Vasistha offers a rational approach to Vedanta, bridging the secular and the sacred.

- Both work and knowledge are essential for liberation.

- The world is a confusion, and realizing its unreality is crucial for freedom from sorrow.

- Self-worth, guided by scripture and holy company, is paramount.

- The mind, with its tendencies and cravings, is the root of bondage.

- Contentment, inquiry, self-control, and good company are gatekeepers to liberation.

- The text explores the nature of time, egotism, and the illusion of the material world.

- The story of Leela illustrates the mind's power to create and perceive reality.

- The ultimate goal is to realize the infinite consciousness that underlies all existence.

Introduction to Yoga Vasistha

The book "Vases as Yoga" is an English translation of the Yoga Vasistha, accompanied by expositions from Swami Venkatasana. The Yoga Vasistha is a spiritual text favored in India for centuries, known for its rational approach and its philosophy of bridging the secular and sacred aspects of life. It emphasizes reason, with the idea that even a child's remark should be accepted if it aligns with reason, while even the creator's words should be rejected if they don't. Swami Venkata Sananda's translation is a service to spiritual seekers, aiming to rescue individuals from worldliness and guide them toward creative living.

Scholarly Speculations and the Direct Experience of Truth

The Yoga Vasistha is presented as a direct aid to spiritual awakening and experiencing the truth. The text contains repetitions that serve to clarify its teachings. A central verse emphasizes that the world's appearance is a confusion, akin to the sky's blueness being an optical illusion, and suggests ignoring it. The scripture encourages direct observation of the mind, its motions, notions, and reasoning, to realize the indivisible unity of consciousness. It asserts its supremacy in guiding one to what is good, emphasizing that the teaching, not the book or sage, is supreme.

Salutations to Reality and the Essence of Yoga Vasistha

The text offers salutations to the ultimate reality, recognizing it as the source of all existence, the unity of knower, knowledge, and known, and the absolute bliss that sustains all beings. The Yoga Vasistha is described as a unique work of Indian philosophy, respected for its practical mysticism and ability to aid in attaining God-consciousness. It's suited for spiritually evolved individuals and contains stories and illustrations that appeal to philosophers, psychologists, and scientists. The scripture, narrated to God himself, imparts true understanding about the creation of the world, aligning with the philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism, which posits that everything is consciousness.

Part One: On Dispassion - The Sage's Question

The sage Agastya is asked whether work or knowledge is more conducive to liberation. The response is that both work and knowledge together lead to liberation, comparing them to the two wings of a bird. Neither work nor knowledge alone suffices, but their combination forms the means to achieve liberation. A legend is introduced about a holy man named Karana, son of Agnivesia, who became apathetic to life after mastering the scriptures.

The Legend of Sarosi and the Royal Sage

A celestial nymph named Sarosi encounters a messenger of Indra, who is on a mission to escort a royal sage engaged in austerities to heaven. The royal sage declines Indra's invitation upon learning that even in heaven, rewards are temporary. Indra sends the messenger again, suggesting the sage seek counsel from the sage Vamukhi. The royal sage asks Vamukhi about the best way to rid oneself of birth and death, leading Vamukhi to narrate the dialogue between Rama and Vasistha.

The Story of Rama as a Raft to Cross the Ocean of Samsara

Vamukhi explains that the dialogue between Rama and Vasistha is for those who feel bound and seek liberation. He reveals that he composed the story of Rama earlier and imparted it to his disciple Baradvaja, who then narrated it to Brahma, the creator. Brahma, pleased, granted a boon to free all human beings from unhappiness and directed Baradvaja to have Vamukhi continue narrating the story of Rama to dispel the darkness of ignorance. Brahma himself, accompanied by Baradvaja, requested Vamukhi to continue the narration, declaring it the raft with which men will cross the ocean of samsara.

The Importance of Studying the Scripture Daily

Vamukhi emphasizes that neither freedom from sorrow nor realization of one's real nature is possible without the conviction that the world appearance is unreal, which arises from studying the scripture diligently. Liberation, or moksha, is the total abandonment of all mental conditioning. Mental conditioning is of two types: pure and impure, with the impure leading to rebirth and the pure liberating one from it. Vamukhi prepares to narrate how Rama lived an enlightened life, which will free listeners from misunderstandings about old age and death.

Rama's Pilgrimage and Subsequent Change

Upon returning from his pilgrimage, Rama, along with his brothers, toured the country and then returned to the capital, delighting the people. However, a profound change came over Rama, causing him to grow thin and weak. Despite his father's concern, Rama remained silent about what was troubling him. Dasaratha turned to the sage Vasistha for answers, who enigmatically suggested that there was a reason for Rama's behavior, as great changes do not occur without cause.

The Arrival of Sage Viswamitra and His Request

Sage Viswamitra arrives at the palace, and King Dasaratha welcomes him, offering to fulfill any wish he may have. Viswamitra reveals that he needs assistance in fulfilling a religious rite, as demons, followers of Kara and Usana, desecrate the holy place whenever he undertakes it. He requests that Rama be sent to deal with these demons, promising manifold blessings in return. Viswamitra emphasizes the importance of duty over attachment to one's son, assuring Dasaratha that Rama is capable and that his help will bring unexcelled glory.

Dasaratha's Reluctance and Vasistha's Intervention

King Dasaratha is stunned by Viswamitra's request, as Rama is not yet sixteen and has not seen combat. He offers himself and his army instead, unable to part with Rama. Viswamitra's anger rises at this reluctance. Sage Vasistha intervenes, persuading the king to honor his promise and send Rama with Viswamitra, assuring him of Rama's safety and the sage's power.

Rama's Dejected State and the Chamberlain's Report

In obedience to Vasistha, Dasaratha orders Rama to be fetched, but the attendant reports that the prince seems dejected. The chamberlain then details Rama's profound change since his pilgrimage: disinterest in bathing, worship, company, jewels, and entertainment. Rama is described as going through motions like an automaton, often muttering about the unreality of wealth, prosperity, and the world, relishing only solitude and lamenting the dissipation of life instead of striving for the supreme. The chamberlain expresses deep distress, noting Rama's lack of hope, desire, and attachment, and his occasional suicidal thoughts.

Viswamitra's Insight and Rama's Arrival

Viswamitra suggests that Rama's condition is not delusion but wisdom and dispassion, and asks for him to be brought forth to dispel his despondency. Rama arrives, saluting his father and the sages, his face shining with maturity. The king embraces him and questions his sadness, warning against dejection. Rama explains that a trend of thought has robbed him of hope in the world, questioning the meaning of happiness in transient objects and the endless cycle of birth and death.

Rama's Disillusionment with Wealth and Lifespan

Rama expresses his disillusionment with wealth, describing it as unsteady, fleeting, and a source of numerous worries. He notes that wealth hardens hearts, gains even the wise, and is incompatible with happiness. He also laments the fleeting nature of lifespan, comparing it to a water droplet on a leaf, and emphasizes that only striving for self-knowledge is worthwhile. To the unwise, knowledge of scriptures is a burden, and without self-knowledge, the body and lifespan are burdens.

Rama's Critique of Egotism and the Restless Mind

Rama describes egotism as the dreadful enemy of wisdom, generating sinful tendencies and actions, and being the sole cause of mental distress. He expresses a desire to rest in the self, free from egotism and desires, realizing that actions driven by egotism are vain. He also critiques the restless mind, comparing it to a lion in a cage, dissatisfied and ever-flitting, unable to find happiness. He laments being bound by cravings and the mind's net, which uproots his whole being and prevents him from resting.

Rama's Lament on Craving and the Pitiable Body

Rama describes craving as enveloping the mind, drying up noble qualities, and driving him astray. He likens it to a gale carrying a straw away, cutting away hope, and making him revolve in a wheel of craving. He notes that craving cannot be appeased, has no direction, and spreads a wide net of relations. He also critiques the pitiable body, comparing it to a tree full of illnesses, worries, and suffering, and expresses his lack of enchantment with it.

Rama's Critique of Childhood and Youth

Rama critiques childhood, highlighting its helplessness, mishaps, cravings, inability to express oneself, foolishness, instability, and weakness. He notes that children are easily offended, angered, and brought to tears, and are subjected to control and punishment. He also critiques youth, describing it as a stage of numerous mental modifications, misery, and the embrace of lust. He notes that youth is the abode of diseases and mental distress, and that it arouses evils and suppresses good qualities.

Rama's Critique of Old Age, Time, and Fate

Rama critiques old age, describing it as a period of slavery to sexual attraction and the body's decay. He notes that old age destroys the body, makes it a laughing stock, and is followed by death. He also critiques time, describing it as merciless, inexorable, cruel, greedy, and insatiable, destroying everything in its path. He questions whether there is any hope for simple folk like him, given the power of time and the inevitability of death.

Rama's Yearning for Wisdom and Liberation

Rama concludes by stating that neither childhood, youth, nor old age bring happiness, and that none of the objects in the world are meant to give happiness. He expresses a desire to wean his heart away from the ever-changing world and to remain at peace within himself. He prays for instruction that will free him from anguish, fear, and distress, and destroy the darkness of ignorance in his heart. He seeks to understand how enlightened beings live in the world and how the mind can be freed from lust.

Rama's Plea for Guidance and the Court's Acclaim

Rama reflects on the pitiable fate of living beings and expresses his confusion and fear. He admits to giving up everything but not establishing himself in wisdom, and seeks guidance on how to reach a state of peace and bliss while involved in worldly activities. He asks how to live in the world without being influenced by experiences, and how to cleanse the mind of impurities. He implores for instruction that will enable his restless mind to be steady and to never again be sunk in grief.

The Sages' Inspiration and the Arrival of More Sages

The assembled court is deeply inspired by Rama's words of wisdom, feeling as if their own doubts and misunderstandings have been dispelled. They acclaim Rama with one voice, and a shower of flowers falls from heaven. The perfected sages in the assembly declare that the answers to Rama's questions are worthy of being heard by all beings in the universe, and hasten to the court to listen to the supreme sage Vasistha.

Part Two: The Behavior of the Seeker - The Story of Sukha

Viswamitra acknowledges Rama's wisdom but suggests it needs confirmation, like Sukha's self-knowledge needed confirmation from Janaka. He narrates the story of Sukha, son of Vedavyasa, who, despite deep contemplation and dispassion, did not find peace until his knowledge was confirmed by the royal sage Janaka. Sukha's journey involved being ignored by Janaka for a week, then being waited upon by dancers and musicians, and finally receiving the same answer from Janaka that he had received from his father, which led to his peace.

The Importance of Confirmation and Vasistha's Instruction

Viswamitra states that Rama, like Sukha, has gained the highest wisdom, and that the surest sign of this is being unattracted by worldly pleasures. He requests that Vasistha instruct Rama to confirm his wisdom, inspiring them all. Vasistha agrees to impart the wisdom revealed to him by Brahma, but Rama first asks why Vedavyasa was not considered liberated while his son Sukha was.

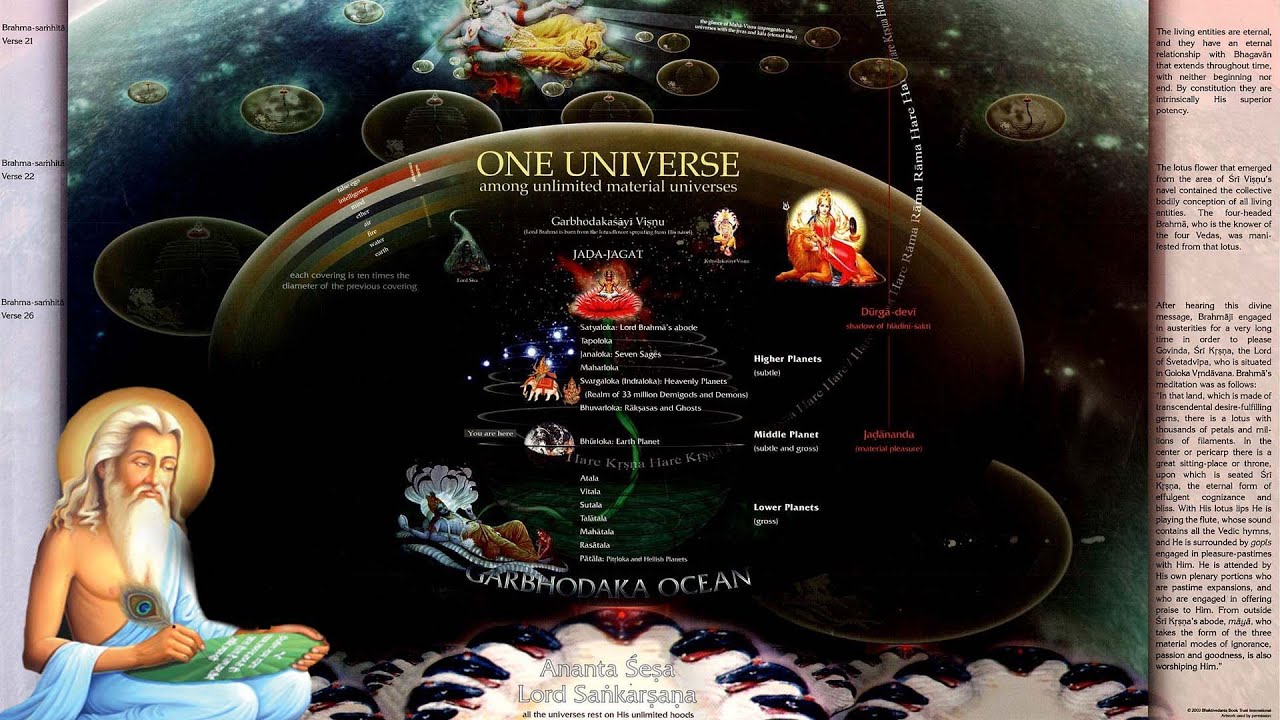

The Nature of Universes and the Liberated Sage

Vasistha explains that countless universes have come into being and dissolved, and that these universes are the creation of desires in the heart. He states that Vedavyasa is indeed a liberated sage, but that liberated sages also embody themselves countless times, assuming relations with others and sometimes being equal or unequal in their learning and behavior. The difference is only in the eyes of the ignorant spectator.

The Power of Self-Worth and the Fictitious Nature of Fate

Vasistha emphasizes that whatever is gained in this world is gained only by self-worth, and that failure indicates slackness in effort. He declares that fate is fictitious and not seen, while self-worth is mental, verbal, and physical action in accordance with scripture. Self-worth is of two categories: past and present, with the latter counteracting the former. He advises correcting deluded action and overcoming evil with good, and fate with present effort, warning against laziness and reveling in sense pleasures.

The Potency of the Present and the Ridicule of Fatalism

Vasistha continues the second day's discourse, stating that effort determines the fruit, which is also known as fate. He emphasizes that the present is infinitely more potent than the past and that those who are satisfied with past efforts are fools. He explains that when present self-worth is thwarted, it indicates weakness, and that a weak man sees the hand of providence when confronted by a powerful adversary. He ridicules fatalism and emphasizes that self-worth springs from right understanding, scripture, and the conduct of holy ones.

The Threefold Root of Self-Worth and the Futility of Fatalism

Vasistha states that one should pursue self-knowledge with a healthy body and mind, as such self-worth has a threefold root and fruit: inner awakening, decision in the mind, and physical action. He emphasizes that fate does not enter here and that those who desire salvation should divert the impure mind to pure endeavor. He ridicules the notion of fate, arguing that if it truly ordained everything, then all action would be meaningless.

The Nature of God, Fate, and Latent Tendencies

Rama asks what people really call God, fate, or divum. Vasistha replies that it is the fruition of self-worth by which one experiences the results of past action. He explains that latent tendencies in the mind give rise to actions, and that one's actions are in strict accordance with these tendencies. He states that one cannot definitely determine whether categories like mind, latent tendencies, action, and fate are real or unreal, and that men of wisdom have alluded to them symbolically.

Freedom of Action and the Importance of Good Tendencies

Rama asks if latent tendencies from previous births impel action in the present, where is freedom of action? Vasistha explains that these tendencies are of two kinds: pure and impure, with the pure leading to liberation and the impure inviting trouble. He emphasizes that one is free to strengthen the pure tendencies and abandon the impure ones gradually. By encouraging good tendencies and strengthening them, the impure ones will weaken, leading to the experience of the supreme truth.

The Cosmic Order and the Story of Vasistha's Enlightenment

Vasistha explains that the cosmic order, which ensures that every effort is blessed with appropriate fruition, is based on omnipresent omniscience known as Brahm. He urges restraining the senses and mind, and listening to a narrative dealing with liberation. He then recounts how, in a previous age, the creator Brahma brought him into being but drew a veil of ignorance over his heart. Miserable, Vasistha begged Brahma to show him the way out, and Brahma revealed the true knowledge that dispelled the ignorance.

The Role of Sages and Kings and the Four Gatekeepers to Freedom

Vasistha explains that in every age, the creator brings forth sages for spiritual enlightenment and kings for secular duties. However, kings are often corrupted by power and pleasure, leading to wars and remorse. To remove their ignorance, sages impart spiritual wisdom to them, known as rajavidya or kingly science. He emphasizes that the highest form of dispassion has arisen in Rama's heart due to the grace of God, which meets the maturity of discrimination. He then introduces the four gatekeepers to the realm of freedom: self-control, spirit of inquiry, contentment, and good company, urging diligent cultivation of these.

The Nature of Liberation and the Importance of Self-Knowledge

Vasistha urges listening to the exposition of liberation with a pure heart and receptive mind, as the miseries of birth and death will not end until the supreme being is realized. He explains that if one overcomes the sorrow of samsara, they will live on earth like a god. When delusion is gone and the truth is realized, the world becomes an abode of bliss, and such a person has nothing to acquire or shun. He emphasizes that such bliss is possible only by self-knowledge, not by any other means.

The Fruits of Self-Control and the Nature of Inquiry

Vasistha explains that to cross the ocean of samsara, one should resort to the eternal and unchanging. He emphasizes that self-control, or conquest of the mind, is one of the four gatekeepers to liberation, and that all good and auspicious things flow from it. He also highlights the importance of inquiry, stating that it is the best remedy for samsara and that it protects one from calamities. He defines inquiry as asking "Who am I?" and "How has this evil of samsara come into being?", leading to knowledge of truth, tranquility, and supreme peace.

Contentment, Satsang, and the Synthesis of Virtues

Vasistha identifies contentment and satsang (company of the wise) as additional gatekeepers to liberation. Contentment, the renunciation of cravings and satisfaction with what comes unsought, leads to purity of heart. Satsang enlarges intelligence and destroys ignorance. He emphasizes that these four virtues are the surest means to be saved from the ocean of samsara, and that diligent practice of one will lead to the others and to the highest wisdom.

The Structure and Significance of the Scripture

Vasistha explains that one endowed with the enumerated qualities is qualified to listen to what he is about to reveal, and that this revelation can lead to liberation even without desire. He outlines the structure of the scripture, consisting of 32,000 couplets divided into sections on dispassion, the behavior of a seeker, creation, existence, cessation, and liberation. He emphasizes that the scripture is easy to comprehend due to its interesting stories and that studying it eliminates the need for austerities, meditation, or mantra repetition.

The Purpose of Parables and the Importance of Direct Experience

Vasistha explains that parables are used to enable the listener to arrive at the truth, and that their significance should not be stretched beyond their intention. He emphasizes that study and understanding of the scriptures with the help of illustrations and a qualified teacher are necessary until one realizes the truth. He also states that direct experience alone is the basis for all proofs, and that wisdom born of inquiry dispels non-understanding, allowing the undivided intelligence to shine in its own light.

Part Three: On Creation - The Threefold Space

The text introduces three important words: tsudakaza, siddiques, and butakasa, representing consciousness space, mind space, and element space, respectively. These concepts are explained by Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi, who states that sadakisa is the image of atma and can only be hewn with the mind. The same infinite consciousness is known as these three spaces viewed from the spiritual, mental, and physical dimensions.

The Secret of Creation and the Illusion of Reality

Vasistha declares that bondage lasts as long as one invests the perceived object with reality, and that bondage goes when that notion goes. He explains that during cosmic dissolution, the entire objective creation is resolved into the infinite being, and that the infinite itself conceives the duality of oneself and the other, leading to the arising of mind. He emphasizes that the mind is non-different from the infinite self, and that clinging to the notion of the reality of "you" and "I" prevents liberation.

The Story of the Holy Man Akasaja and the Nature of Karma

Vasistha narrates the story of Akasaja, a holy man born of space, whom death could not grasp because he had no karma. Yama explains to death that one's own karma causes death, and that Akasaja, being born of space, had no previous birth or mind, and therefore no karma. He is described as pure consciousness, with no notion that can give rise to karma.

The Spiritual Nature of the Creator and the Creation

Vasistha explains that the creator has no memory of the past, no physical body, and is of spiritual substance. The creator's thought is the cause of the manifold creation, and the creation is of the nature of thought without materiality. A throbbing in the creator brought into being the subtle body of intelligence of all beings, made only of thought. The creator is of a dual nature: consciousness and thought, with consciousness being pure and thought subject to confusion.

The Nature of the Mind and the Illusion of the Universe

Rama asks what the mind really is, and Vasistha replies that it is empty nothingness, whether real or unreal, and that it is what is apprehended in objects of perception. He states that thought is mind, and that the self clothed in the spiritual body is known as mind, which brings the material body into existence. He emphasizes that the entire universe is forever non-different from the consciousness that dwells in every atom, and that when this notion is firmly rejected, consciousness alone exists.

The Source of the Mind and the Nature of the Supreme Self

Rama asks about the source of the mind and how it arose. Vasistha explains that after cosmic dissolution, the entire objective universe was in perfect equilibrium, and there existed the supreme Lord, the eternal unborn. From him emerged countless divinities and infinite worlds. He is the cosmic intelligence in which countless objects of perception enter, and the light in which the self and the world shine. This supreme self cannot be realized by means other than wisdom, and it is realized in oneself as the experience of bliss.

Realizing the Lord and the Unreality of the Universe

Rama asks where the Lord dwells and how to reach him. Vasistha replies that the Lord is the intelligence dwelling in the body and that he is the universe, though the universe is not him. He explains that the Lord can be realized only if one is firmly established in the unreality of the universe. He emphasizes that dualism presupposes unity and that only when the creation is known to be utterly non-existent is the Lord realized.

The Method to Know the Truth and the Characteristics of the Liberated

Rama asks by what method this is known and what he should know to end the knowable. Vasistha replies that the wrong notion that the world is real can be removed by resorting to the company of holy men and studying holy scripture. He explains that when the truth is realized, one thinks of it, speaks of it, rejoices in it, and teaches it to others. He then describes the characteristics of jivanmuktas (liberated while living) and videhamuktas (liberated ones who have no body).

The Nature of Divine Will and the Story of Sukha

Rama asks what people really call God, fate, or divum. Vasistha replies that it is the fruition of self-worth by which one experiences the results of past action. He explains that latent tendencies brought forward from previous births are of two kinds: pure and impure, with the pure leading to liberation and the impure inviting trouble. He emphasizes that one is free to strengthen the pure tendencies and abandon the impure ones gradually.

The Cosmic Being and the Creation of the Universe

Vasistha explains that a cosmic order ensures that every effort is blessed with appropriate fruition and is based on omnipresent omniscience known as Brahm. He states that this narrative deals with liberation and that listening to it will lead to the realization of the supreme being. He then describes how, when a vibration arises in the cosmic being, Lord Vishnu is born, and from Vishnu, Brahma the creator was born, who began to create the countless varieties of beings in the universe.

The Creator's Compassion and the Revelation of True Knowledge

Vasistha explains that the creator saw that all living beings were subject to disease, death, pain, and suffering, and sought to lay down a path that might lead them away from all this. He instituted centers of pilgrimage and noble virtues, but these were inadequate. Reflecting thus, the creator brought Vasistha into being, drew him to himself, and drew the veil of ignorance over his heart. In response to Vasistha's prayer, Brahma revealed the true knowledge that dispelled the ignorance.

The Importance of Dispassion and the Four Gatekeepers to Freedom

Vasistha states that in every age, the creator wills into being several sages for spiritual enlightenment. He explains that the highest form of dispassion, born of pure discrimination, has arisen in Rama's heart and is superior to dispassion born of circumstantial causes. He emphasizes that as long as the highest wisdom does not dawn in the heart, the person revolves in the wheel of birth and death. He then reiterates the four gatekeepers to the realm of freedom: self-control, spirit of inquiry, contentment, and good company.

The Nature of Liberation and the Importance of Self-Knowledge

Vasistha urges listening to the exposition of liberation with a pure heart and receptive mind, as the miseries of birth and death will not end until the supreme being is realized. He explains that if one overcomes the sorrow of samsara, they will live on earth like a god. When delusion is gone and the truth is realized, the world becomes an abode of bliss, and such a person has nothing to acquire or shun. He emphasizes that such bliss is possible only by self-knowledge, not by any other means.

The Fruits of Self-Control and the Nature of Inquiry

Vasistha explains that to cross the ocean of samsara, one should resort to the eternal and unchanging. He emphasizes that self-control, or conquest of the mind, is one of the four gatekeepers to liberation, and that all good and auspicious things flow from it. He also highlights the importance of inquiry, stating that it is the best remedy for samsara and that it protects one from calamities. He defines inquiry as asking "Who am I?" and "How has this evil of samsara come into being?", leading to knowledge of truth, tranquility, and supreme peace.

Contentment, Satsang, and the Synthesis of Virtues

Vasistha identifies contentment and satsang (company of the wise) as additional gatekeepers to liberation. Contentment, the renunciation of cravings and satisfaction with what comes unsought, leads to purity of heart. Satsang enlarges intelligence and destroys ignorance. He emphasizes that these four virtues are the surest means to be saved from the ocean of samsara, and that diligent practice of one will lead to the others and to the highest wisdom.

The Story of Leela and King Padma

Vasistha begins the story of Leela and King Padma, describing Padma as a righteous and worthy king and Leela as his beautiful and accomplished wife. Leela, devoted to her husband, sought to ensure their eternal life together. She consulted holy ones and decided to propitiate the goddess Saraswati to obtain a boon that her husband's jiva would not leave their palace after his death.

Leela's Penance and the Boons Granted by Saraswati

Leela began her penance to propitiate the goddess Saraswati, maintaining her service to her husband while undertaking this spiritual practice. After 100 such three-nightly worships, Saraswati appeared before her and granted her two boons: that her husband's jiva would remain in the palace after his death, and that she would be able to see Saraswati whenever she prayed.

The Death of King Padma and Saraswati's Guidance

King Padma died from wounds sustained on the battlefield, leaving Leela inconsolable. An ethereal voice, Saraswati, instructed her to cover the king's body with flowers to prevent decay and ensure he would not leave the palace. Still unsatisfied, Leela invoked Saraswati, who appeared and explained the three types of space: psychological, physical, and the infinite space of consciousness. Saraswati advised Leela to meditate intensely on the infinite space of consciousness to experience her husband's presence, even though she could not see him physically.

Leela's Meditation and the Vision of King Padma

Leela meditated and entered the highest state of consciousness, the infinite space of consciousness. There, she saw King Padma on his throne, surrounded by kings, sages, women, and armed forces. However, they could not see her, as thought forms are visible only to oneself. She also saw members of Padma's court, leading her to wonder if they were also dead. By Saras