Brief Summary

This video provides a comprehensive overview of the pharmacology of drugs used in the treatment of anemia. It begins by explaining the physiology of red blood cell production and iron metabolism, then discusses the various causes of anemia and their corresponding treatments. The video covers iron therapy, vitamin B12 and folate, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, HIF stabilizers, specialized therapies for specific types of anemia, and treatments for hemolytic anemia and iron overload. The key takeaway is that effective anemia treatment relies on identifying the underlying mechanism and selecting the appropriate therapy to address the specific defect.

- Red blood cell production and iron metabolism are essential for understanding anemia treatments.

- Anemia can result from deficiencies, impaired production, marrow suppression, or excessive destruction of red cells.

- Treatment strategies include replacing missing substrates, stimulating red cell production, or counteracting pathological destruction.

Introduction

The video introduces the topic of anemia and the drugs used in its treatment. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the physiology behind red blood cell production and iron metabolism as a foundation for understanding therapeutic approaches. The video will cover various medications and strategies used to combat anemia.

Red Blood Cell Production & Iron Metabolism (Physiology)

Red blood cells, or erythrocytes, are produced in the bone marrow through erythropoiesis, starting with pluripotent stem cells that differentiate into erythroid progenitors. Erythropoietin (EPO), a hormone primarily made by the kidneys, stimulates this maturation. When oxygen delivery to renal tissue decreases, specialized paratubular cells secrete more EPO, which then binds to receptors on early red cell precursors in the marrow, preventing apoptosis and stimulating proliferation. Healthy erythropoiesis depends on iron, vitamin B12, folate, bone marrow function, and supporting cytokines. Iron metabolism is also crucial, with most iron absorption occurring in the duodenum and upper jejunum. Dietary non-heme iron is reduced to the ferrous form and transported into enterocytes by DMT1, where it can be stored as ferritin or exported to plasma via ferroportin. In the bloodstream, iron binds to transferrin, which delivers it to tissues, particularly the marrow, for hemoglobin synthesis. Hepsidin, a peptide hormone produced by the liver, regulates systemic iron balance by controlling ferroportin degradation, thus reducing iron export into plasma when iron levels are high or inflammation is present.

Understanding the Causes of Anemia

Anemia occurs when the equilibrium of red blood cell production and destruction is disrupted. Common causes include iron deficiency from blood loss or malabsorption, vitamin B12 or folate deficiency leading to megaloblastic changes, impaired EPO production as seen in chronic kidney disease, marrow suppression from toxins or chemotherapy, chronic inflammation that traps iron, and excessive destruction of red cells in hemolytic states. Understanding the underlying mechanism is crucial for guiding drug therapy, which aims to replace missing substrates, stimulate red cell production, or counteract pathological destruction.

Iron Therapy

Iron therapy is the cornerstone treatment for iron deficiency anemia. Oral preparations like ferrous sulfate, ferrous gluconate, and ferrous fumarate supply iron 2+, which is absorbed in the duodenum via DMT1. These salts differ mainly in their elemental iron content per dose and their tendency to cause GI side effects. Absorption is greatest in an acidic, empty stomach environment and is enhanced by vitamin C. Common adverse effects include nausea, constipation, abdominal discomfort, and dark stools. Intravenous iron products such as iron sucrose, ferric gluconate, ferric carboxymaltose, ferumoxytol, and iron dextran are preferred when rapid iron repletion is required or when intestinal absorption is reduced. These complexes are taken up by macrophages in the reticuloendothelial system, which then slowly hand iron off to transferrin, limiting free reactive iron in plasma. While generally safe, rapid iron release or immune reactions can cause transient hypotension, flushing, or, rarely, severe hypersensitivity reactions.

Vitamin B12 & Folate

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) and folate (vitamin B9) work together in DNA synthesis and nerve health. B12 acts as a methyl carrier in the methionine synthase reaction, taking a methyl group from methylated folate and passing it to homocysteine to form methionine, which frees folate for DNA synthesis. A lack of B12 traps folate in its methylated form, reducing usable folate levels and leading to megaloblastic anemia. B12 deficiency can also cause neurologic problems like numbness and gait disturbance due to its role in maintaining myelin. Folic acid, after absorption, is converted into active folate forms, including methylfolate, which transfers methyl groups to vitamin B12. These active forms supply the one-carbon units needed to build purines and thymidine for DNA synthesis. Inadequate folic acid intake or conversion impairs DNA synthesis in rapidly dividing bone marrow cells, leading to megaloblastic anemia without the neurologic damage seen in B12 deficiency. Giving folic acid alone can correct the anemia in B12 deficiency, but the underlying nerve injury continues to worsen if B12 is not replaced.

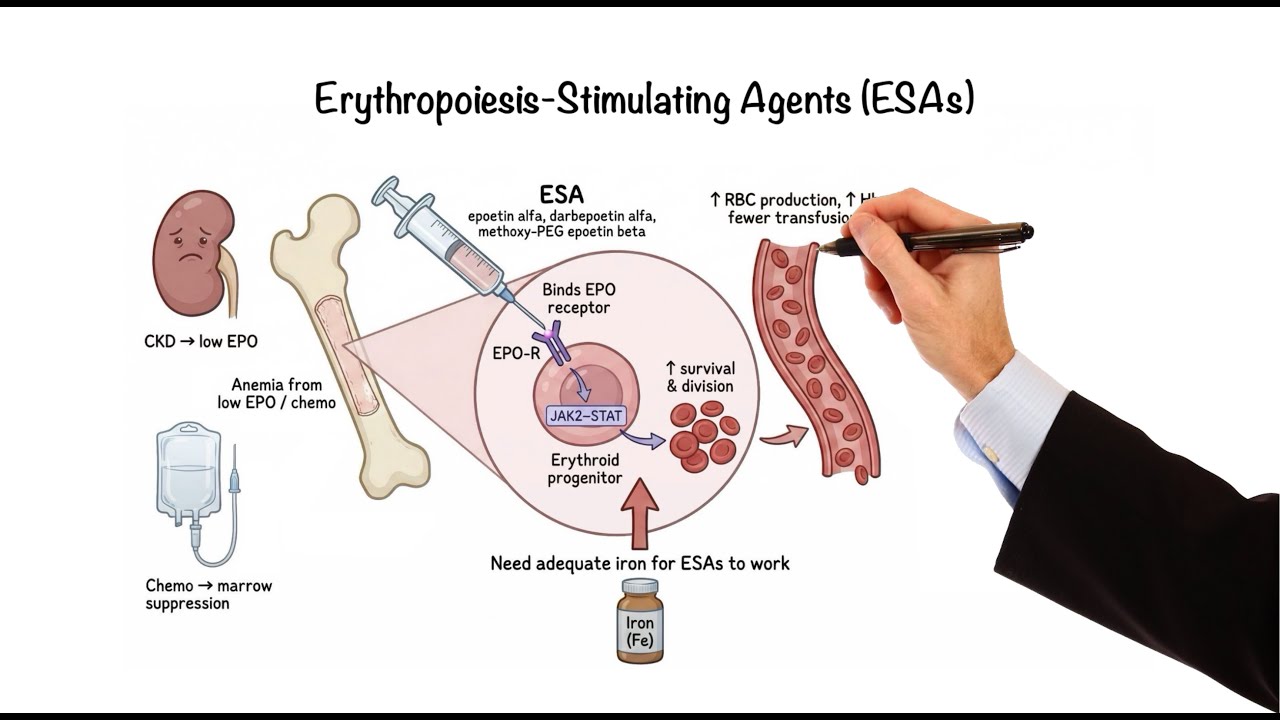

Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents

For patients with anemia due to insufficient erythropoietin production, such as those with chronic kidney disease or chemotherapy-related marrow suppression, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) can be life-changing. Recombinant ESAs like epoetin alpha, darbepoetin alpha, and methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta are lab-made versions of EPO. They bind to erythropoietin receptors on erythroid progenitor cells in the bone marrow, triggering JAK-STAT signaling, which helps these cells survive and divide, increasing red blood cell production and reducing the need for transfusions. However, if hemoglobin levels rise too high or the dose is too aggressive, the risk of hypertension, thrombosis, and stroke increases, so a moderate hemoglobin target is preferred. Adequate iron stores are essential because the marrow quickly uses available iron, and without enough iron, the response to ESAs will be poor.

HIF Stabilizers

HIF (hypoxia-inducible factor) stabilizers represent a newer strategy for anemia of chronic kidney disease by increasing the body's own EPO production and improving iron use. These drugs target the HIF system, which allows cells to sense low oxygen and adjust gene expression. Under normal oxygen conditions, prolyl hydroxylases add hydroxyl groups to the HIF alpha subunit, tagging it for degradation, so very little HIF remains active. When oxygen is low or when prolyl hydroxylase is blocked, HIF alpha accumulates, moves into the nucleus, and turns on genes that increase erythropoietin synthesis in the kidney and increase iron-handling proteins. Oral HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors like roxadustat and vadadustat stabilize HIF alpha, causing endogenous EPO levels to rise and the liver to make less hepcidin, which releases iron from stores and improves absorption. The net effect is more red blood cell production with better iron availability using the body's own regulatory pathway instead of recombinant hormone. These oral agents can be a convenient alternative to injections for some patients, but like ESAs, they may increase the risk of hypertension, thrombosis, and possible electrolyte problems, so their long-term safety is still being studied.

Specialized Therapies (Sideroblastic, Thalassemia, MDS)

Beyond iron replacement, vitamins, ESAs, and HIF stabilizers, some anemias require more specialized approaches that target specific blocks in red blood cell production. In hereditary sideroblastic anemia, the defect is in the first step of heme synthesis in the mitochondria, where the enzyme ALA synthase uses vitamin B6 as a cofactor. High-dose pyridoxine can boost the residual activity of ALA synthase in B6-responsive cases, improving heme production and red blood cell production. In transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia and certain myelodysplastic syndromes, the main problem is ineffective erythropoiesis at the late stages of maturation. Luspatercept, a fusion protein, acts as a ligand trap for selected transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) superfamily ligands, such as activins and GDFs, which normally slow late erythroid differentiation. By binding these ligands, luspatercept lets late erythroid precursors in the bone marrow mature more effectively, raising hemoglobin levels and reducing transfusion needs, even though the underlying genetic defect remains.

Hemolytic Anemia & Iron Overload

In hemolytic anemias, red blood cells are destroyed faster than the bone marrow can replace them, so the pharmacologic goal is to remove the trigger and slow red cell clearance, not simply to stimulate erythropoiesis. If hemolysis is drug-induced, stop the offending agent; if infection is driving it, treat the infection. In autoimmune hemolytic anemia, antibodies bind to red cells and mark them for macrophage-mediated removal. Corticosteroids reduce hemolysis by dampening immune activation and decreasing antibody-driven clearance. If hemolysis persists, rituximab targets CD20 on B cells to reduce autoantibody production upstream. Folate supplementation is often used to support nucleotide synthesis during accelerated erythropoiesis. When hemolysis is severe or symptomatic, packed red blood cell transfusions rapidly restore oxygen-carrying capacity, but repeated transfusions add iron that the body cannot actively excrete. For chronic transfusion exposure, iron chelation may be needed with deferoxamine as a parenteral chelator and deferasirox as an oral option, both binding excess iron for elimination to prevent iron overload complications.

Summary

Treating anemia starts with identifying the mechanism and choosing the therapy that fixes that specific defect. Iron restores the raw material for hemoglobin, and vitamin B12 and folate restore DNA synthesis for normal red cell maturation. When the erythropoietic signal is low, ESAs and HIF stabilizers increase erythropoiesis by boosting EPO activity and improving iron availability. For select disorders, pyridoxine supports heme synthesis in B6-responsive sideroblastic anemia, and luspatercept lifts the brake on late red cell maturation. When anemia is driven by destruction or marrow failure, the focus shifts to stopping the cause, using immunosuppression when appropriate, and supporting with transfusions with iron monitoring and chelation if transfusions become chronic.