Brief Summary

This video provides an overview of pharmacodynamics, explaining how drugs interact with the body at the molecular level. It covers different types of receptors (ligand-gated ion channels, G protein-coupled receptors, enzyme-linked receptors, and intracellular receptors), drug actions (agonists, antagonists), and key concepts like EC50, Emax, and therapeutic index.

- Receptor types and their mechanisms of action

- Agonists, antagonists, and their effects on receptors

- EC50, Emax, and therapeutic index as measures of drug potency, efficacy, and safety

Intro

Pharmacodynamics studies what a drug does to the body, focusing on the interactions between drugs and cell receptors. When a drug enters the body, it interacts with cell receptors, leading to a signal formation. This signal initiates a series of reactions that ultimately result in a biological effect, such as halting DNA replication.

Receptor types

Cells have various receptors that produce unique responses when stimulated. The four main types of receptors with therapeutic relevance are ligand-gated ion channels, G protein-coupled receptors, enzyme-linked receptors, and intracellular receptors.

Ligand-gated ion channels

Ligand-gated ion channels feature a ligand-binding site. When a ligand binds, the channel opens briefly, allowing ions like sodium, potassium, chloride, and calcium to pass through the membrane.

G protein-coupled receptors

G protein-coupled receptors (also known as seven-transmembrane receptors) pass through the cell membrane seven times and consist of three subunits: alpha, beta, and gamma, collectively known as the G protein. In its inactive form, the alpha subunit has GDP attached. When a ligand binds, GTP replaces GDP, causing the alpha subunit to dissociate from the beta-gamma complex. Both complexes then interact with and regulate other enzymes or proteins, leading to a response. The three important types of G proteins are Gs (stimulatory), Gi (inhibitory), and Gq. Gs activates adenylyl cyclase to produce cyclic AMP (cAMP) from ATP, Gi inhibits adenylyl cyclase to lower cAMP levels, and Gq activates phospholipases C (PLC). PLC produces diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol triphosphate (IP3) as second messengers. DAG activates protein kinases, while IP3 mediates intracellular calcium release. G protein-coupled receptors can amplify signals, where one stimulated receptor activates many adenylyl cyclases, resulting in more cAMP molecules and an amplified response.

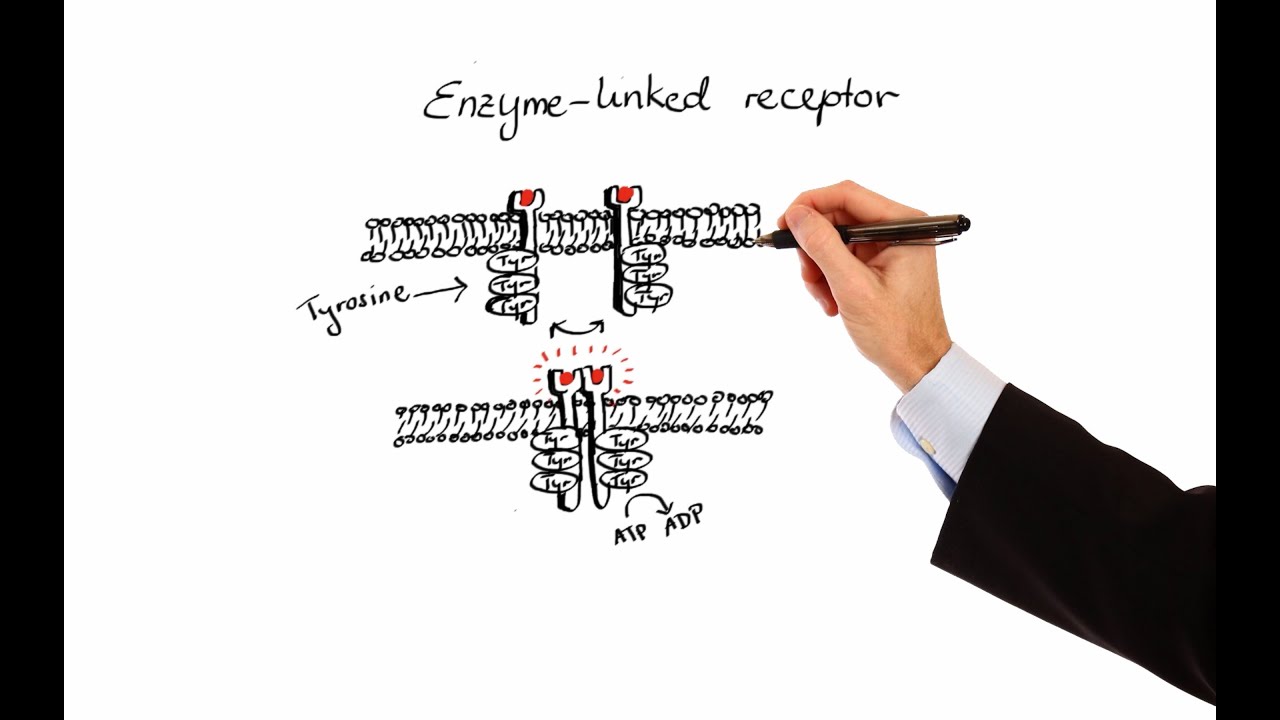

Enzyme-linked receptors

Enzyme-linked receptors have an extracellular binding site where a ligand, typically a hormone or growth factor, attaches to stimulate enzymatic activity inside the cell. Most are tyrosine kinase receptors, meaning they display kinase activity involving the amino acid tyrosine. When a ligand binds to two receptors, it causes a conformational change, leading to aggregation and dimer formation. The tyrosine regions are activated, converting ATP to ADP and resulting in autophosphorylation of the receptors. Inactive intracellular proteins attach to the phosphorylated tyrosine, causing conformational changes and a cascade of activations that produce a cellular response.

Intracellular receptors

Intracellular receptors are located inside the cell rather than on the cell membrane. The ligand must cross the lipid membrane to bind to the receptor. The activated ligand-receptor complex can then move into the nucleus, bind to DNA, and regulate gene expression, ultimately leading to the synthesis of specific proteins. Cells can downregulate receptors by removing them from the membrane and recycling them, decreasing sensitivity to signaling molecules. Conversely, cells can upregulate receptors by inserting more receptors into the membrane, increasing sensitivity to signaling molecules.

EC50 & Emax

As the concentration of a drug increases, its pharmacologic effect also increases until all receptors are occupied. EC50 is the concentration of a drug that produces 50% of the maximal effect, indicating the drug's potency. A drug with a lower EC50 is more potent. Emax represents the maximum efficacy of a drug, assuming all receptors are occupied. A drug with a higher Emax is more efficacious.

Agonists

Intrinsic activity refers to a drug's ability to produce a maximal effect. A full agonist can produce a maximal effect comparable to the body's endogenous ligand. Basal activity is the activity shown by about 15% of receptors even without an agonist. A partial agonist cannot produce a maximal effect even when occupying all receptors. An inverse agonist binds to receptors and stabilizes them in their inactive form, eliminating basal activity.

Antagonists

An antagonist binds to a receptor and blocks it, reducing agonist activity. A competitive antagonist competes with the agonist for the same binding site, shifting the dose-response curve to the right and reducing potency (increasing EC50). Some antagonists form covalent bonds with the active site, irreversibly blocking it in a non-competitive process, which reduces maximal effect (Emax) and efficacy. Allosteric antagonists bind to a different site from the agonist, inducing a conformational change that prevents agonist activation, also reducing Emax but not changing EC50.

Therapeutic index

The therapeutic index measures the relative safety of a drug, calculated as the ratio of the dose that produces toxicity in 50% of the population (TD50) to the dose that produces an effective response in 50% of the population (ED50). The therapeutic index represents the range of doses at which a drug provides benefits without causing major toxicity.