Brief Summary

This video provides a comprehensive overview of Patanjali's Yoga Sutras, explaining the core principles of yoga as a science of the mind. It covers the four books of the Yoga Sutras: Samadhi Pada (contemplation), Sadhana Pada (practice), Vibhuti Pada (accomplishments), and Kaivalya Pada (absoluteness). The video details the nature of the mind, the importance of controlling thoughts, and the path to achieving ultimate freedom and peace through yoga.

- Yoga is primarily a science of the mind, not just physical exercises.

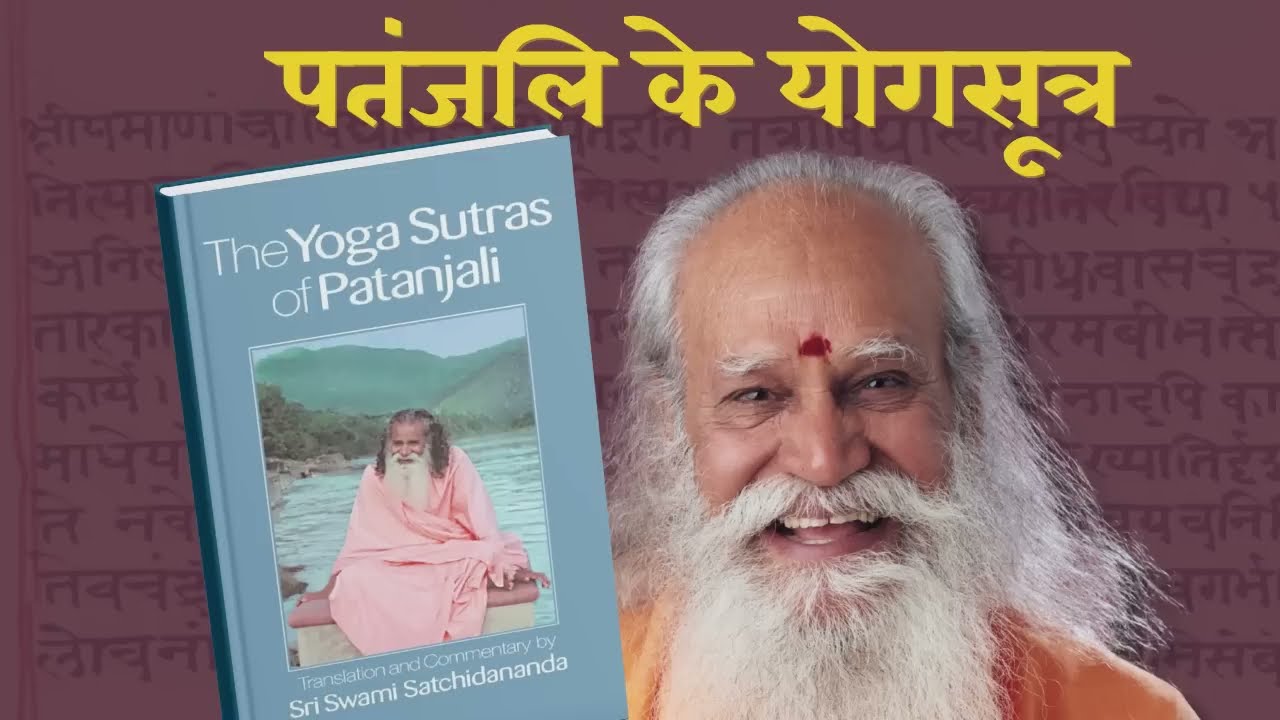

- The Yoga Sutras, written by Patanjali, are the main text for understanding and practicing Raja Yoga.

- The ultimate goal of yoga is to control the fluctuations of the mind and realize one's true self.

- Practice (Abhyasa) and detachment (Vairagya) are essential for achieving mental stillness.

Introduction (परिचय)

Most people think of yoga as physical exercises to stretch the body and reduce stress, but this is a small and recent part of yoga. Physical yoga, or Hatha Yoga, was created to make the practice of real yoga easier, which involves understanding and gaining complete control over the mind. Yoga is essentially the science of the mind, helping individuals understand how their minds work and how to manage them effectively. Ancient Raja Yoga explores how to understand and control the mind, questioning whether our minds dictate our experiences or if we can shape their functions.

Book One: Samādhi Pāda (समाधि पाद) (Portion on Contemplation)

The study of Raja Yoga or Ashtanga Yoga begins here, which is yoga with eight limbs. The Yoga Sutras, as explained by Patanjali, are the most significant and primary scripture of yoga. Patanjali connected the principles of yoga with meditation and explained them to his disciples, who took notes in brief, concise words known as sutras. These sutras, which literally mean "thread," are collections of words, often incomplete sentences, that clearly outline the entire science of yoga, including its goals, necessary practices, obstacles, solutions, and expected outcomes. The first sutra, "Atha Yoga Anushasanam," means "Now, the exposition of yoga is being made," indicating that Patanjali is providing a direct method for practicing yoga, not just philosophical concepts. The second sutra defines yoga as the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind, emphasizing that controlling these fluctuations leads to the experience of yoga.

The term "yoga" typically means union, but in this context, it refers to the unique experience of yoga achieved by stopping the changing states of the mind. "Chitta" refers to the entire mind complex, which includes ego, intellect, and the sensory mind. The sensory mind perceives external stimuli, the intellect processes this information, and the ego reacts based on these inputs. Normally, individuals exist in a calm state, but the fluctuations of the mind disturb this peace. External experiences are shaped by these mental fluctuations, which can transform a stranger into a father based on a shift in perception. Yoga does not focus on changing the external world but on controlling one's thoughts, as true freedom and bondage exist within the mind.

When the mind is stilled, one can experience their true self, separate from the body and mind. The "seer" or true self is neither the body nor the mind but the knower or observer. To understand this true self, the mind must be calm, like a clear mirror reflecting an image without distortion. Otherwise, the mind's fluctuations alter the perception of reality. In daily life, individuals often identify with their thoughts and bodies, losing sight of their pure self. By detaching from these identifications, one can see the pure "I," where there is no difference between individuals. This unity extends beyond humans to all things, living and non-living, as everything is interconnected through a single, unchanging consciousness or energy.

The mind has five types of fluctuations, or vrittis, which can either cause suffering or be without suffering. These vrittis include right knowledge, wrong knowledge, imagination, sleep, and memory. Patanjali divides these vrittis into those that cause suffering and those that do not, noting that even pleasurable thoughts can lead to suffering later. Selfish thoughts ultimately cause suffering, while selfless thoughts lead to peace. The goal is not to empty the mind entirely but to cultivate good, selfless thoughts and eliminate harmful, selfish ones. By understanding and managing these thoughts, one can achieve inner peace and happiness.

Patanjali identifies three means of valid knowledge: direct perception, inference, and testimony from reliable sources, including scriptures, saints, or gurus. Direct perception involves firsthand experience, while inference draws conclusions based on observations, such as inferring fire from smoke. Testimony relies on the words of trusted individuals who have realized the truth. While these methods provide knowledge, the ultimate goal is to transcend them to achieve inner peace. This involves recognizing and discarding thoughts, both good and bad, to reach a state of mental stillness.

Misconceptions arise when knowledge does not align with reality, such as mistaking a rope for a snake in dim light. Imagination, or " विकल्प" (vikalpa), involves constructing ideas from mere words without any basis in reality. Sleep is a state where the mind is based on the experience of nothingness, and memory is the retention of past experiences. To control these vrittis, practice (abhyasa) and detachment (vairagya) are essential. Practice involves consistent effort to maintain mental stillness, while detachment involves separating oneself from the causes that bring about these vrittis.

Consistent practice, performed over a long period, without interruption, and with full devotion, strengthens one's ability to control the mind. Detachment involves controlling desires by thinking critically about whether something is beneficial. Attachment to desires colors the mind and creates disturbances, hindering continuous practice. Therefore, both practice and detachment are necessary for achieving mental stillness. The highest form of detachment comes with the realization of the true self, which brings such profound joy that previous desires fade away.

Sampragyata Samadhi involves discernment and is characterized by reasoning, reflection, joy, and pure egoism. It requires a mind that is already disciplined and focused. This state is further divided into four types based on the levels of nature: gross objects, subtle elements, the mind itself, and ego. Asampragyata Samadhi is achieved by stopping all mental activity, leaving only impressions or latent impressions (samskaras). This leads to complete freedom, where the individual is no longer bound by the world.

Those who achieve partial control over nature through Sampragyata Samadhi may become deities or merge with nature, but they must eventually return to attain full knowledge and liberation. For others, Asampragyata Samadhi can be attained through faith, strength, memory, meditation, and wisdom. The time it takes to achieve Samadhi depends on the intensity of the practice. Another path to Samadhi is through devotion to Ishvara (God), who is free from suffering, actions, and desires, and is the source of all knowledge. Ishvara is the guru of all gurus, transcending time.

Ishvara's name is Om, which encompasses both name and form, representing the infinite and all-encompassing nature of the divine. Om consists of three letters: A, U, and M, representing creation, preservation, and destruction. The repetition of Om and contemplation of its meaning is a powerful practice for attaining Samadhi. Obstacles on the path to Samadhi include physical illness, mental lethargy, doubt, negligence, laziness, sensory indulgence, false knowledge, and instability. To overcome these obstacles, focusing on one thing is the best method.

Cultivating positive emotions such as friendliness towards the happy, compassion towards the suffering, joy towards the virtuous, and indifference towards the wicked helps maintain mental peace. Controlling and observing the breath can also lead to mental stability. Focusing on subtle sensory experiences, such as a fragrance or taste, can further stabilize the mind. Alternatively, one can focus on an inner light or the mind of an enlightened being. Ultimately, Patanjali advises focusing on whatever brings peace and stability to the mind.

Through consistent practice, mastery extends from the smallest atom to the largest entity, attracting the entire creation. As the mind becomes pure, it reflects the true nature of reality, leading to Samadhi, where the knower, the object of knowledge, and the process of knowing become one. This section concludes by describing different types of Samadhi, including Savitarka Samadhi (with deliberation), Nirvitarka Samadhi (without deliberation), Savichara Samadhi (with reflection), and Nirvichara Samadhi (without reflection), emphasizing the importance of purifying the mind to achieve true liberation.

Book Two: Sādhana Pāda (साधन पाद) (Portion on Practice)

This section focuses on practical aspects of yoga, starting with Kriya Yoga, which includes Tapas (discipline), Svadhyaya (self-study), and Ishvara Pranidhana (surrender to God). Tapas involves accepting and purifying oneself through life's difficulties, rather than seeking only pleasure. Svadhyaya involves studying scriptures that remind one of their true self, and Ishvara Pranidhana means dedicating all actions and their fruits to God or humanity. These practices help reduce obstacles and prepare for deeper states of meditation.

The five Kleshas (afflictions) that cause suffering are ignorance (avidya), egoism (asmita), attachment (raga), aversion (dvesha), and clinging to life (abhinivesha). Ignorance is the root of all other afflictions, leading to egoism, attachment, aversion, and fear of death. These afflictions can be dormant, weakened, intercepted, or fully active. The goal is to weaken and eliminate these afflictions through consistent practice and self-awareness.

Ignorance involves mistaking the impermanent for the permanent, the impure for the pure, and the non-self for the self. By recognizing the true nature of reality, one can detach from these false identifications and achieve inner peace. Egoism arises from identifying the true self with the mind and body. Detachment involves recognizing that the true self is separate from these changing aspects. Attachment and aversion arise from the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain. By understanding that true happiness lies within, one can reduce attachment to external things.

Clinging to life arises from the fear of death, which stems from past experiences. By understanding the cycle of birth and death, one can reduce this fear and live more fully in the present. Karma, generated by these afflictions, bears fruit either in the present or future lives. Actions create impressions (samskaras) that accumulate and determine future experiences. By understanding the nature of karma, one can strive to perform selfless actions and reduce future suffering.

The cycle of karma includes three types: Prarabdha (karma that is currently bearing fruit), Agami (karma that is being created in the present), and Sanchita (accumulated karma from past lives). While Prarabdha karma must be experienced, one can influence Agami and Sanchita karma through conscious actions. The goal is to purify the mind and eliminate the root cause of karma, which is ignorance.

The section also discusses the nature of the seen (Prakriti) and the seer (Purusha). Prakriti consists of the three gunas (Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas) and provides experiences for Purusha. By distinguishing between Purusha and Prakriti, one can achieve liberation. This involves recognizing that the true self is separate from the changing aspects of nature. The practice of yoga helps to purify the mind and reveal the true self.

The section concludes by discussing the eight limbs of yoga: Yama (ethical restraints), Niyama (observances), Asana (posture), Pranayama (breath control), Pratyahara (sense withdrawal), Dharana (concentration), Dhyana (meditation), and Samadhi (absorption). Yama includes Ahimsa (non-violence), Satya (truthfulness), Asteya (non-stealing), Brahmacharya (continence), and Aparigraha (non-possessiveness). Niyama includes Shaucha (purity), Santosha (contentment), Tapas (discipline), Svadhyaya (self-study), and Ishvara Pranidhana (surrender to God). These practices form the foundation for deeper states of meditation and Samadhi.

Book Three: Vibhūti Pāda (विभूति पाद) (Portion on Accomplishments)

This section discusses the accomplishments (Vibhuti) that arise from the practice of the last three limbs of Raja Yoga: Dharana (concentration), Dhyana (meditation), and Samadhi (absorption). Dharana is the practice of fixing the mind on a single object or idea, which is the beginning of meditation. Dhyana is the continuous flow of the mind towards that object, maintaining a constant connection. Samadhi is the state where only the object of meditation shines forth, as if devoid of its own form.

The combination of Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi on the same object is called Samyama, which leads to knowledge and power. By performing Samyama on different aspects of nature, one can gain various Siddhis (powers). These powers include knowledge of the past and future, understanding the language of all beings, knowledge of past lives, understanding the thoughts of others, invisibility, and the ability to traverse space.

The section also describes specific Samyamas that lead to particular powers, such as gaining strength by focusing on the strength of an elephant, gaining knowledge of the universe by focusing on the sun, and understanding the arrangement of the stars by focusing on the moon. By focusing on the navel chakra, one gains knowledge of the body's constitution, and by focusing on the Kuma Nadi, one achieves steadiness. Focusing on the light above the head leads to visions of accomplished beings.

The section emphasizes that while these powers are attainable through yoga, they can also be obstacles to true Samadhi. The ultimate goal is to transcend these powers and achieve Kaivalya (liberation). This involves detaching from the Siddhis and maintaining a clear distinction between the mind and the true self. The section concludes by describing the state of liberation, where the qualities of nature (Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas) cease to have any influence, and the soul rests in its true form.

Book Four: Kaivalya Pāda (कैवल्य पाद) (Portion on Absoluteness

This section discusses the state of Kaivalya, or complete independence, which is the ultimate goal of yoga. Siddhis (powers) can be attained through birth, herbs, mantras, austerity, or Samadhi. However, the most natural and lasting Siddhis come from the correct practice of yoga and Samadhi. The transformation from one species to another occurs through the power of nature, and the development of nature happens automatically.

The mind is the cause of other constructed minds, and different minds may have different activities, but the master is the same. Actions of the mind born of meditation are free from impressions. For the yogi, actions are neither white (good) nor black (bad), while for others, actions are of three kinds: good, bad, and mixed. From these three, only manifestations of those desires for which conditions are favorable appear. Though separated by class, space, and time, there is no break in the relation between memory and impression because of the sameness of form.

Because the desire to live is eternal, impressions are without beginning. Held together by cause, effect, support, and object, when these cease, impressions cease to exist. The past and the future exist in their own form, possessing attributes. The essence of things is unity, and change is in the qualities. Perception differs as minds are different. An object is not dependent on one mind; what would become of it when that mind did not perceive it?

An object is known or unknown according to the coloring of the mind. The state of the mind is always known because the soul is unchangeable. The mind is not self-luminous because it can be known. The mind cannot know itself and another object at the same time. If one mind is perceived by another, there would be an endless number of minds and confusion of memory. The soul's essence never changes. When the mind takes its form, the mind knows itself.

Colored by the seer and the seen, the mind understands all. Existing for another, even when desire ceases, the mind is still perceived. For one who sees the difference, the illusion of the self ceases. Then the mind is inclined towards discrimination and gravitates towards liberation. Thoughts may arise from habit. These are to be destroyed like the others. For one who is wise and does not desire even the highest results, comes the cloud of virtue, धर्ममेघसमाधि (Dharma-megha-samadhi).

From that comes cessation of pain and works. Then, knowledge, being infinite, has little more to learn. The qualities, having fulfilled their object, become latent in nature. The succession of changes is cognizable at the end. The soul is established in its own glory, and that is liberation. The video concludes with a prayer for all to experience the peace and joy of yoga through the grace of Maharishi Patanjali, urging viewers to go beyond books and know the truth through their own hearts and experiences.